In the industrial era, the Factory was the manufacturing & social hub: a place where workplace and community co-existed. However, with technology rapidly evolving within all reaches of society, the work-model of the Factory has disintegrated, and become disconnected with social activity. The post-industrial era abandons the Factory to its isolated location, causing land value and industrial importance to fall dramatically.

This proposal seeks to re-imagine the Factory as a catalyst of social and physical importance. It sees the role of the Factory as a machine to fuse an interface between social and physical barriers through its application of spatial organisation and proposed programme.

Technology has been widely accepted and adapted to most industries, but within the construction world, the use of technology is under-developed. With the lack of housing in the UK, it raises the question of whether embracing recent technologies could pave the way to producing houses quickly and efficiently whilst retaining high quality design.

This project incorporates both digital fabrication and social engagement under one roof, resulting in the inhabitTM Factory - a dedicated facility that produces a CNC cut modular housing system. This provides housing to surrounding neighbourhoods in Thamesmead, the profits of which feed back into the Community Land Trust that occupies the site. This is the model that then funds business engagement and social activity under the same Factory roof.

This project challenges the role of the Factory today and how it could become a place for both social interaction and the celebration of digital technology, to help solve social and political issues both within Thamesmead and across the UK.

THE COLLABORATIVE CATALYST

MArch II | Research, Thesis, Design & Exhibition

PROBE

Digital technology has transformed the way architects work over the last 20 years. Architectural drawing has evolved from the drawing board, into 2D computer CAD work and most recently into the availability of BIM. The design industry has accepted digital changes, which in turn have created more complex designs that perhaps require a rethink of the traditional construction techniques. The construction industry has not developed at the same pace which is limiting the potential advances created by the new digital technologies.

COMMUNITY

ARCHITECT

The architect usually plays a key role in most of large construction projects, but with large housing schemes, the developer generally controls the project. It is the architect’s responsibility to achieve the best design for the client and users’ needs, yet this can sometimes be lost if a developer is overpowering. Solving the housing crisis will need rework of the current model, including developers accepting the input of architects, innovative construction techniques and input from users to develop ground breaking solutions.

FUTURE?

PRESENT

PAST

DEVELOPER

COUNCIL

Thamesmead is a large area in East London that began development in the 60s. Thamesmead is cut off from the rest of London due to a lack of transport infrastructure and the nature of the phyiscal barriers. The river and the railway split Thamesmead and in a sense create an island. It has very limited transport connections back to central London, resulting in heavy car and bus use in the area. Due to failure to complete the original masterplan, it can be seen as a series of distinct architectural styles that house a diverse demographic. Negative connotations with the area have arisen with the release of dystopian films like Clockwork Orange, and the use of the Southmere Estate concrete towers as the backdrop to crime documentaries, resulting in hostility towards the media and outsiders.

This industrial site represents the fragmentation of Thamesmead through physical barriers of railways, roads & infrastructure, and also social barriers of the prisons & industrial units.

Can the existing social & physical infrastructure be used to integrate this area, instead of fragment? Site frontages will be redefined, and programme rethought.

SITING

Thamesmead territorial mapping provides an analysis of community-centred areas, and highlights the "dead-zones" or no-go areas that exist today. An overlay of the land ownership starts to suggest reasons behind this fragmentation and highlights key areas for development opportunity. We therefore focus on industry, which is limited to the peripheries of the town.

MOTION

THE COLLABORATIVE CATALYST || A CHALLENGE TO THE CONCEPT OF "FACTORY"

PRODUCTION LAYER

SOCIAL LAYER

MULTI-USE FACTORY || PROGRAMMATIC FUSION

inhabitTM || PRODUCTION PROCESS

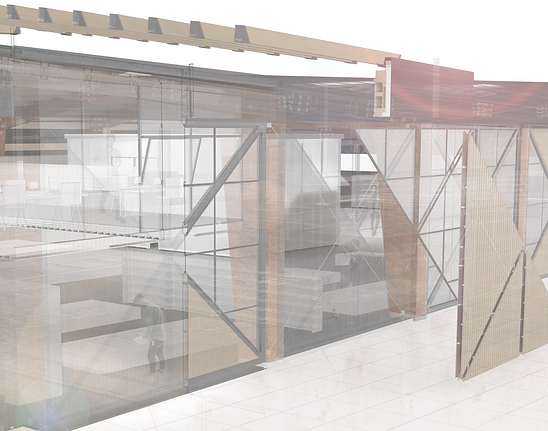

The main function of the Collaborative Catalyst is the production of modular housing: inhabitTM, which is set in the main factory hall, using digital construction techniques.

The production system is arranged in a linear pattern for efficiency. There are key features throughout the building where there is engagement with the public through different architectural interventions, such as a raised public gantry taking members of

the public through the production cycle in a safe and controlled manner.

inhabitTM || SOCIAL LAYER

The social route through the building is more organic throughout compared to the linearity of the production cycle. The social aspects weave throughout the building, allowing for exploration of different technologies and processes in the building, whilst also opening up what is commonly a private production process to encourage interest and community engagement.

In each area, special consideration was given to the level of accessibility to, and visibility of, the production processes to maximise safe interaction at all times.

ECONOMIC MODEL // COLLABORATIVE CATALYST CHARTER

The economic model for the running of this site is broken down into three main segments: production, social provision and rentable space.

The site is managed by the CCC – Collaborative Catalyst Charter. This not-for-profit company ensures the sustainable regeneration of this industrial area of Thamesmead. The charter seeks to encourage and protect social activity across all aspects of the regeneration works by setting strategies that consider the social issues in Thamesmead. The site is set up as a community land trust, so the community own and controls the land, giving control of this area back to its residents. Different user groups pay into the policy in different ways, and in turn gain the facilities and benefits that the site offers.

The Factory produces houses for the people which are sold to the communities in Greenwich, and the profit feeds back into the CCC. This money can then continue to fund the other functions on site. The requirements of the 21st Century Factory in Thamesmead, therefore, is to build houses, provide specialist facilities and workspace for the local businesses, support and encourage education, and provide local community groups with amenities & opportunities for social activity.

Standard practice defines the house as something that is usually heavily customised, with personalisation and bespoke elements. In contrast, industrial units are standardised using repetitive portal frames to produce a cheap and adaptable open-plan space.

The Collaborative Catalyst flips the common architectural notions of both a house and a factory. To create a social hub, these roles are reversed, creating a simple housing system which is accessible for all, and a bespoke, designed factory to create a social beacon in Thamesmead.

PROPOSITION

Across the different scales of the project, there are links through similar timber joint systems, adapted as required due to the scale of the design. The scale of these three structures make them appear to be different, yet looking closely at the joints, you can see how each have been carefully designed and inspired by each other.

TAXONOMY OF DETAILS // ACROSS THE SCALES

CONSTRUCTION DRAWINGS // FROM FACTORY TO MODULE

Stepping of scale requires different levels of construction information. The modular units have been designed specifically to be constructable by those without experience, whereas the factory has a different brief.

The modular system is cut from 21mm Kerto plywood using a CNC machine. Each element is designed as simple flat-pack joints, which lock together without the needs of bolts and nails. The house is simple and easy for anyone to assemble using the step-by-step construction manual.

The multi-use space is seen as a hybrid of the two structural techniques, using a glulam frame system, but with repetitive joints. The base frame is like a standard portal frame, with bespoke joints for the roof, to tie it together with the permanent factory building.

The permanent factory frame mimics the house and constructed using GluLam frames and bespoke metal joints. Since the factory frame is the permanent feature, the frame is adapted and designed to address the site and functions within according to the necessary ventilation and lighting required.

ENVIRONMENTAL STRATEGY // BESPOKE DESIGN

The bespoke factory has been designed carefully to maximise the use of sunlight and shading and natural ventilation, to create a comfortable workspace to be in. Each frame is bespoke and designed to create space beneath that suit the needs of the internal and external functions.

The cladding differs in each bay according to internal function, but the panels containing glazing have openable panels at either the high or lower levels on the north façade, with high level vents on the south façade. Ventilation can travel through the building from north to south, or through single-sided ventilation, entering low and drawn out through the upper openings.

The roof of the factory is designed to maximise light in the south-facing courtyard to the north of the factory building. Th twisting form creates peaks and troughs that cast shadows into the less public-orientated areas of the courtyard.

Polycarbonate cladding on the south facade is set back to account for the different sun paths at different times of the year. In summer, when the sun is higher, and the sunlight doesn’t hit the polycarbonate, reducing solar heat gain inside the factory. During winter months the building can take advantage of solar heat gain due to the lower sun angle.

WORKING METHOD// ACROSS THE SCALES

Although at each scale of design we began by assessing space in 2D, as we progressed through the development of the masterplan and our individual

proposals, 3d design became an important tool for both visualising space and addressing site context.

PHASING AND FORM // 1:1000 SITE MODEL

BUILT FORM // 1:6 MODULAR SYSTEM TESTING

SPATIAL QUALITY AND MATERIALITY // 1:200 FACTORY MODELLING

IMPACT

ARCHITECT

DEVELOPER

COUNCIL

With the introduction of Crossrail into Abbeywood, developers are capitalising on the comparatively cheap land prices and are developing schemes that are aimed at commuters and city workers, thanks to the new direct links to central London. These developments are most commonly aimed at the private sector rather than affordability.

A meeting with Averil Lekau, the Cabinet Minister for Housing and Anti-Poverty for Greenwich, highlighted the extent of the problem in this borough: there is currently a 16 year waiting list for council housing in Greenwich, and that number is looking likely to increase. If developers continue the trend of meeting the minimum quota of “affordable” housing, it does nothing to improve the situation for those without homes. The issue is building for profit, vs. building for communities.

It is not for the Developer to say how a community will live and work. Developments often fail due to their inability to react to the changing needs of a community. The Collaborative Catalyst gives this developer power to the people of Thamesmead, and provides an adaptable system made possible by the implementation of digital technology. The result: an interdependent community of workers, creatives, researchers, educators and innovators that are provided with the tools to build their spaces for working, connecting, and living.

COMMUNITY

DEGREE SHOW